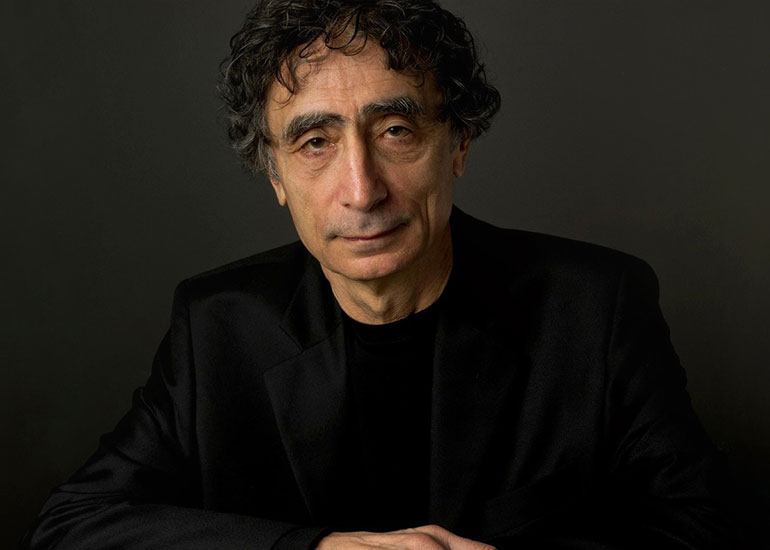

Gabor Maté (pronunciation: GAH-bor MAH-tay) is a retired physician who, after 20 years of family practice and palliative care experience, worked for over a decade with patients challenged by drug addiction and mental illness. The best-selling author of four books published in twenty-five languages, including the award-winning In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, Gabor is an internationally renowned speaker highly sought after for his expertise on addiction, trauma, childhood development, and the relationship of stress and illness. Gabor: Trauma is a word that's used by a lot of people, and some people have a narrower definition than I do. When you look at the original word trauma, it's a Greek word for wounding. Wherever we're wounded, there's scar tissue that forms, and scar tissue is always harder, less resilient, and less flexible than the tissue that it replaces. When psychological trauma happens, our psyches become more rigid and harder and less flexible. The origin of that hardening is the separation from the self that trauma induces, and then rather than being flexible and responsive, we become more rigid in our responses to life, to ourselves, to relationships, to stimuli, and so on. This is what I think underlies most mental and physical pathology. Gabor: Catastrophic events like that are traumatic in their impact, and if some people want to use the word trauma just for those kinds of events, I'm okay with that. I'll just have to find a new word for what I'm talking about. In my definition, it's not what happens to you externally that defines the trauma but what happens internally to you as a result of it. That pain and wounding can happen when a little infant is not picked up when they're crying. That child experiences a wound, and there will be a corresponding constriction in the psyche and in the self. There will also be compensatory mechanisms to prevent that pain from happening again. Those mechanisms could be trying to be pleasant and nice to others while ignoring one's own feelings, or it could be trying to soothe oneself through various behaviors. Kids may rock themselves or suck their thumbs or masturbate or overeat and then later on may use drugs. With those compensations one is either trying to make oneself more acceptable to others by constricting one's own self-expression, or trying to soothe the pain when it becomes too much. Either way, it's a pathology. Gabor: The mind and the body can't be separated. It's not that there's a psyche that's separate from our physiology. It's that both the psyche and the physiology are part and parcel of our organism and are designed for survival. They're inseparable, so whatever happens psychically happens on a deep physiological level. If I were to scream at you right now, that would profoundly change your physiology in a split second, even though we're talking on the phone in two different places and I can't possibly hurt you. Your emotions would affect changes in your autonomic nervous system, your cardiovascular system, your gut, your immune system, in your blood vessels, in your muscles. In other words, everywhere. That's the temporary change that would happen in you, and as soon as the threat is removed—either I stop yelling or you hang up on me—your physiology will gradually, depending on your resilience, come back to normal. But what if children live in a situation where this happens chronically? What's it like for a child, night after night, not to be picked up when they're crying? This is often the advice of doctors—let them cry themselves to sleep. What's it like for a little kid to be yelled at? There's still a debate about spanking, although there shouldn't be anymore, but what's it like for a little kid to be hit by an adult five times as big as they are when these adults are designated by nature to be their protectors and safekeepers? When our psyches are under chronic stress, that puts our physiological system under stress as well. That's the first point. The second point is that when we don't get the acceptance that is our natural birthright, and our parents for whatever reason of their own are not able to grant us that despite their best wishes perhaps, then we adjust to their expectations because we have to maintain that relationship. One way to maintain that relationship is to be compliant. That calls for a repression of one's own feelings because one doesn't feel nice all the time. And so the only way you can survive is to not even be aware of when you're angry, because otherwise you might express it. Well, we know that the suppression of anger can actually disable or at least hobble the immune system. So a lot of people who repress their healthy anger end up with autoimmune diseases which, by the way, might explain the fact that 80% of people with an autoimmune disease are women. Early stress and early trauma also triggers inflammation in the body. It triggers inflammatory processes that are measurable in adulthood. Inflammation predisposes people to malignancy and autoimmune disease. So there are multiple mechanisms. A lot of the details need to be worked out, but conceptually, the connection has been very elegantly demonstrated. Gabor: There are multiple ways in, but it begins with the recognition that the healing process is necessary and possible. What all good healing processes have in common is reconnecting you with yourself, both on the emotional and the physiological levels. Whether you look at Somatic Experiencing, expressive dance, EMDR, Brainspotting, Internal Family Systems, or my particular work, Compassionate Inquiry, it's all about reconnecting people with their authentic feelings and emotions. Just a few weeks ago, I found myself in the shoals of some psychological travail, so I called up a breath therapist and I've started a daily breath practice. It can even be something on that simple level. Gabor: In general, if the pregnancy goes well, we're born unburdened. We don't have any conscious awareness of this, but that's who we are. Unburdened. Then the burdens start piling on. People talk about being reborn, but what does that mean? It means you're unburdened again; you're yourself again, without all this stuff that you accumulated that has crusted over your true self. Gabor: Addiction is a complex psychophysiological process. It's manifested in any behavior that a person finds temporary pleasure or relief in, and therefore craves, but that they can't give up despite the negative consequences to themselves or those around them. It's craving pleasure and relief in the short term despite the harm in the long term. It could be any behavior, from drugs and substances of all kinds to sex, gambling, shopping, the internet, video games, eating, pornography, work, extreme sports—anything, even meditation and spiritual work. Gabor: That's right. Like I mentioned, just two weeks ago I found myself up against it again, but I can tell you there's much more in my kit bag right now than there ever was, and when these states arise, I'm able to recognize them as memory states rather than reflecting the present. But it's true—intellectual understanding by itself does not lead to transformation. People often will say to me, "Thank you, your book has changed my life." And my response is, "That's great, maybe I should read it myself." For all that I'm able to articulate these things, it doesn't mean that I've worked them through to the end. Working them through is different than an intellectual understanding. Gabor: Healing comes from an Anglo-Saxon word for wholeness. If trauma is disconnection, then healing is reunification or the discovery of the embodiment of that connection. It's becoming whole again, where you're not split into all these defensive parts of you that are running your life. It means you're not running around trying to soothe the pain all the time by means of drugs or sex or gambling or whatever; you're not running away from yourself all the time by being always on the internet; you're not trying to please people so they'll like you. Instead, you consider what you want, what you prefer, what you feel—not in a selfish way of ignoring others, but also not in a way that ignores you either. This interview was conducted on behalf of 1440 Multiversity by Jenn Brown—a freelance writer, editor, producer, and educator.

1440: You suggest that underlying all dysfunction, including disease and addiction, is an alienation or separation from ourselves caused by trauma. What do you mean by that?

1440: So something doesn't have to be catastrophic—like a car accident or physical abuse—to be considered a trauma?

1440: How does it happen that an emotional hurt leads to a physical pathology? What is the mechanism behind this?

1440: Given all this, how do you look at the healing process?

1440: Who is the self that we are finding in these healing processes? What is our authentic self?

1440: One of these crusts that you do a lot of work with is addiction. How do you define addiction?

1440: It seems as if an understanding of how trauma may have caused our addictions doesn't necessarily lead to healing. Is that true?

1440: So what does it mean to you to heal?

Stay Informed

Sign up and receive insider offers and flash sales in your inbox every week