Sharon Salzberg is a renowned Buddhist meditation teacher and author. A New York Times best-selling author, Sharon has most recently written the compelling book Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection. She is a monthly columnist for On Being, and hosts The Metta Hour podcast for the Be Here Now Network. With Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, Sharon cofounded the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts—one of the most prominent and active meditation centers in the West. If you can get more specific, that's even better, like "I feel exhausted." I'd then encourage the exercise of taking apart the sense of broken. What does that mean? Try to be quite specific. What do you feel physically? "I feel this weight on my chest." "I feel my shoulders are slumping." "I feel like there's pressure in my head." What's the type of mood? "I feel really sad." "I actually feel really hopeless, and I'm so tired." "I feel insufficient to meet the challenge of life." Take apart the feelings. As we take them apart, even though everything we find might sound negative, the difficulties we're facing then become an alive system. It's not like one solid, congealed, unchanging mass, you know? We begin to see it is a moment of this, and a moment of that, and a moment of something else, and that shifts things right there. When we notice the changing nature of whatever we're feeling, there's a kind of liberation that comes with it. The experience is not forever. It's not. Even within itself, it's moving. Every time we feel frightened, or we feel broken, or we feel depressed, I also encourage the experiment of switching from calling those states bad or wrong or terrible to recognizing them as painful, because that's what they actually are. They're very painful states. We can't control, and so the big question becomes how we relate to what comes up. We spend an awful lot of time feeling we should be in control, like "I shouldn't feel this" and "I shouldn't feel that" and "I shouldn't have that thought," but none of that is realistic. So, if we really want to feel happier and have more energy and more connection to real life, then we need to shift the way that we pay attention. Often the thinking loop is fueled by anxiety, or anticipation, or fear. We can learn to go beyond that by asking, "What am I feeling?" and then shifting into an awareness of the body. That will bring you into much more direct experience of the feelings and help you identify what's most important. And sometimes we repeat a thought pattern to avoid the accompanying feeling, because the feeling is uncomfortable—and most of us have not been trained to sit with an uncomfortable feeling. So sometimes thinking instead of feeling becomes our habit, instead of learning to actually sit with discomfort. We're so heady. Ultimately, it leaves us incomplete if we can't also take in all the feeling that's generating the obsessive thinking.

1440: Let's talk about heartbreak. How do you suggest people handle this (often overwhelming) experience?

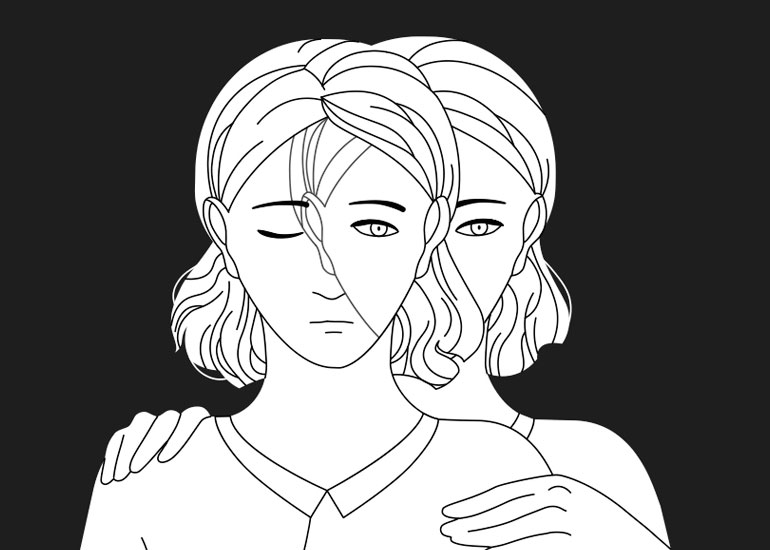

Sharon: When I hear someone say their heart is broken, or they are broken, I might suggest the experiment—as you hear this incantation of "I'm broken" in your mind—of substituting "feel," as in, "I feel broken."1440: Often, heartbreak is accompanied by efforts to "get over" a relationship or an experience. What do you think of that?

Sharon: I guess the risk of it is that we can't actually control what will arise in our minds. We can affect what arises in our minds, and we can work with why we see certain things as failure, instead of as a lesson learned, for example. But can we insist that we're going to be "over" something and never feel a certain way again? No. We cannot guarantee there will never be a memory of that person with accompanying grief.1440: When we hurt, we often get stuck in our minds replaying the same tragedy over and over. Or perhaps we obsess over our actions, or those of another person. What is this about? Why do we do it?

Sharon: I don't entirely know. I think it's probably a combination of things. In more traumatic circumstances, I've often wondered if we repeat thoughts because we can't quite believe the truth of something, and so we're almost trying to tell ourselves: This really happened. This really happened.This interview was conducted by Kate Green Tripp, Managing Editor for 1440 Multiversity.

Stay Informed

Sign up and receive insider offers and flash sales in your inbox every week